Space and process are the two curatorial strands running through the third Singapore Biennale. Conceived around the idea of “Open House” by artistic director Matthew Ngui and curators Russell Storer and Trevor Smith, the Biennale eschews an overtly issue-based approach in favour of probing the conditions that shape art-making, specifically how individual practices negotiate notions of space – both in terms of a physical locality and a contingent sphere of social relations. Underpinning the approach are two simultaneous acts of “opening”: the first referring to that of artistic practice, the second, to that of the city-space, through which the artist-outsider is invited to engage its peculiarities. In considering the albeit simplistic binary that contemporary biennales fall into – either esoteric in its city-specificity or overstretched in its pursuit of a global theme – this gesture of “opening” forms a middle ground, bringing together the local and the cosmopolitan.

The approach reflects a point of maturation for the young Biennale which has previously adopted the vague themes of “Belief” and “Wonder”. The results, however, prove to be rather uneven, for there still remains an overriding tendency for the curatorial formula to defer to the ineluctable obligation to please. Spanning four venues – the National Museum of Singapore (NMS), the Singapore Art Museum (SAM), the Old Kallang Airport and Marina Bay – the Biennale features an eclectic albeit modest range of works, of which the more successful are those that move beyond a mere staging of process towards an interpenetration of practice and site.

Exemplifying this is Thai artist Arin Rungjang’s Unequal Exchange/No Exchange Can Be Unequal, an installation at the Old Kallang Airport modeled after an IKEA showroom with an intriguing contract at work: on weekends, Thai migrant workers from the lower socio-economic stratum are invited to swap the urbane furniture with items brought from their homes. The acts of displacement the artist initiates, performed by a group of displaced individuals no less, become a sculptural gesture as the showroom transforms into a vault of personal artifacts over time. As the indexes of consumption are reclaimed by those toiling at the production end of the consumerist chain, we witness a temporal reconfiguration of social relations, a redressing of inequalities – the hallmark of social sculpture.

Nearby, we witness another act of displacement: in German Barn, artists Elmgreen and Dragset implant within the cavernous hangar a mock-Tudor barn – an icon of quaint rusticity incongruous to the metropolitan sprawl of Singapore. Inside, four shirtless boys sit upon haystacks in a display of homoeroticism and unproductive labour: spatial intervention becomes an institutional critique on the existing order.

Artists in the News (2011), Koh Nguang How, Installation with newspaper archive and on-going research

Meanwhile, at SAM, local artist-archivist Koh Nguang How’s Artists in the News, an installation-archive of newspaper articles documenting twenty years of local art history, sees space and process fusing into a symbiotic union, for the word “archive” itself connotes both a place and an act. The artist replicates the configuration of his apartment where he stores his collection, through which he highlights how the act of archiving implicates space-based processes of placement and classification – both in terms of the personal space of memory and the public space of history.

Also notable are the works that take a broader outlook of “site”, figuring it not merely in terms of an specified locality, but as nodes within a larger network of shifting geographies and temporalities, with the artist assuming the role of the “nomad”. Taking the term from Nicolas Bourriaud’s essay, “Altermodern”, such artists operate practices that are “vehicular, exchange-based and translative”, transforming ideas and signs as they are being transported from one place to another.[1]

South Korean artist Kyungah Ham’s embroideries, for instance, offer a compelling example of the ways artistic process negotiates and circumvent cross-border geopolitical sensitivities. Her embroideries, some of which include images of nuclear explosions, are designed by the artist and handmade by artisans from North Korea – an arduous process involving the transportation of the designs and completed works in parts to avoid rousing the suspicions of the censorial regime. The resulting work is poignant but decidedly anti-auratic, its presence fragmented and thus all the more precious.

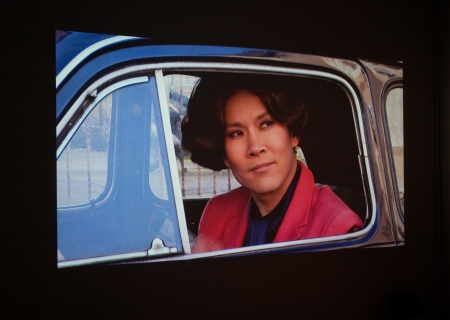

Apart from space and time, this nomadism of the artist can also occur between signs in a semiological system. A simultaneity of all three movements – spatial, temporal, semiological – can be seen in Ming Wong’s ambitiously conceived video installation, Devo Partire. Domani, a recreation of the Pasolini’s cult classic, Teorema. The work, in an act of deliberate miscasting, features the artist playing all of the characters of the film – a characteristic feature of Wong’s practice which often involves mining the archive of world cinema for images of alterity. Crucially, the reenactments here transcend parody and mere exposures of performativity; they constitute an opening of the structures of performance, cinema and by extension, identity. A crucial move here is the splitting of the video into five channels, each playing in a different room, thus spatialising the cinematic montage and demanding the viewer to reconstitute it temporally by way of his or her physical participation in the installation. The filmic encounter turns both processual and spatial.

However, the curatorial formula falters when the processual becomes processional – a tendency that is understandably difficult to circumvent given how the format of a Biennale naturally lends itself to the building of spectacles. Gosia Wlodarczak’s Frost Drawing for Kallang, for instance, marker drawings on the windows of the airport that trace the shifting vistas, forms pretty constellations that are unfortunately only mere illustrations of process. Similarly, Michael Lin’s What a Difference a Day Made, a recreation of a daily goods store, displayed along with the crates in which the wares were shipped to Singapore and video footage of a performer juggling the various wares, appears like a vacuous charade, with the power relations surrounding these commercial items failing to gain a tangible expression. Most conspicuous is Tatzu Nishi’s overhyped The Merlion Hotel, a luxurious hotel constructed around the emblematic Merlion sculpture. While compelling in its professed intent of collapsing public and private space, the work, like the monument that inspired it, ended up as a disingenuous tourist spectacle. But, as an afterthought: can this degeneration into kitsch possibly be construed as “process”?

The works at NMS bear the greatest disjuncture from the Biennale’s overall direction. Exhibited within a large, black and minimally partitioned gallery, they inhabit a nebulous void, decontextualised architecturally and curatorially and yoked into a bewildering concatenation. Shao Yinong and Mu Chen’s massive embroideries of obsolete currencies in Spring and Autumn (2004-2010), for one, appear too glossy under the theatrical setting. Compared to Ham’s more understated works, the political overtones here are significantly obscured by spectacle. Likewise, Teppei Kaneuji’s delicate figures in his White Discharge series, created first by amassing numerous consumer items, followed by their pseudo-taxonomic classification and abstraction with carefully dripped white resin, lose their complexity amidst the environmental pressure to see them plainly as visual curios. Outside, artist collective ruangrupa’s mini-exhibition, Singapore Fiction, which displays artifacts, images and anecdotes accumulated by the artists during their sojourn in Singapore, appears superficial in its methods. While entertaining, the postmodern hodgepodge it presents seems symptomatic of a half-hearted anthropological venture devoid of rigour.

The Biennale’s examination of space and process is certainly a worthy one, especially when seen against the contemporary surfeit of manufactured imagery, of which the truth of its production is often concealed by inscrutable veneers. One could only hope the endeavour was pursued with greater gumption, giving up some of the sheen to make room for works that are more inchoate, in which the negotiations between space and process are not expressed as mere postures, but actual dialogues that unfold in the encounter between art, spectator and site.

The Singapore Biennale 2011 was held from 13 March to 15 May 2011.

Notes

[1] Nicolas Bourriaud, “Altermodern” in Altermodern: Tate Triennial 2009, ed. Nicolas Bourriaud (London: Tate Publishing, 2009), 23.